Summary

Money matters in 2026 not simply as a means of payment, but as a system that determines stability, choice, and resilience in a fast-changing digital economy. Rising living costs, flexible work models, and AI-driven industries have made financial decisions more interconnected with everyday life than ever before. Understanding the role money plays today helps individuals protect their options tomorrow rather than react to crises later.

Introduction: When “Enough” Quietly Becomes Unclear

For much of the past decade, conversations about money focused on earning more, spending less, or finding the next opportunity. In 2026, the question has shifted. The real concern for many students, professionals, and independent workers is no longer how to get rich, but how to stay secure, adaptable, and in control while costs rise faster than certainty.

What many discussions still miss is that money is not only about accumulation. It functions as a buffer against volatility, a tool for decision-making, and a signal of personal leverage in a system increasingly shaped by automation and remote work. When finances are fragile, even small disruptions—health issues, contract gaps, regional price spikes—can force life decisions that feel rushed or misaligned.

This makes the importance of money in life less about status and more about timing, autonomy, and long-term thinking. The value lies not in how much is earned at a single moment, but in how well resources support choices across changing circumstances.

Money as a Stability Engine in an Unpredictable Economy

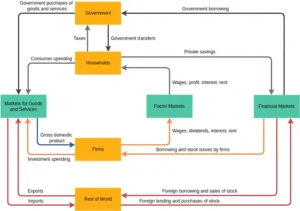

The modern economy rewards flexibility, but it also transfers risk downward. Short-term contracts, gig-based income, and project work offer freedom while removing traditional safety nets. In this environment, money quietly replaces what institutions once provided by default.

Financial stability now acts as a personal shock absorber. It absorbs delays in payment, market downturns, and unexpected transitions without forcing immediate compromise. This is why financial security and stability have become core life priorities rather than abstract goals.

A crucial but often overlooked point is that stability is not binary. It exists on a spectrum. Someone with moderate savings, manageable debt, and predictable expenses may feel more secure than a higher earner living with constant volatility. Money’s role here is functional: it smooths timing mismatches between income and obligations.

This framing changes how success is evaluated. Instead of focusing solely on income growth, experienced professionals increasingly assess how money reduces fragility. The question becomes whether finances allow time to respond thoughtfully instead of reacting under pressure.

How Money Shapes Everyday Decision-Making

Money influences decisions long before purchases occur. It determines which opportunities feel available, which risks feel tolerable, and which paths feel closed off.

Consider career choices. A role with slower growth but predictable income may be dismissed as unambitious, yet it often provides the financial footing that enables side projects, skill-building, or relocation later. Conversely, high-risk opportunities feel empowering only when there is a financial margin for error.

The same dynamic applies to education, housing, and health. Money and quality of life are closely connected not because spending creates happiness, but because financial capacity reduces tradeoffs. When money is scarce, choices become reactive. When it is managed well, decisions become intentional.

This reframes money as a decision amplifier rather than a goal. It does not define values, but it determines how easily values can be acted upon. That distinction is often what separates long-term satisfaction from short-term relief.

The Modern Meaning of Financial Freedom

Financial freedom meaning has evolved significantly. It no longer implies permanent leisure or early retirement for most people. Instead, it reflects the ability to choose work, timing, and direction without constant financial pressure.

In 2026, financial freedom often looks like:

- The ability to walk away from a misaligned job without immediate panic

- The capacity to invest in learning when industries shift

- The option to reduce hours temporarily without destabilizing life

This version of freedom is quieter but more realistic. It is built through consistency rather than extremes. Importantly, it also acknowledges limits. Not every strategy suits every income level or life stage, and chasing freedom too aggressively can introduce new risks.

A common misconception is that freedom requires eliminating all constraints. In practice, it comes from understanding which constraints are acceptable and funding around them. Money enables that negotiation.

Digital Money, Real Consequences

Managing money in the digital economy introduces complexity that previous generations rarely faced. Automated subscriptions, algorithmic pricing, digital wallets, and platform-based income streams blur the line between convenience and opacity.

Digital systems reduce friction but also hide patterns. Small recurring costs accumulate unnoticed. Variable income arrives irregularly. Taxes, benefits, and protections differ across platforms and regions. This makes passive neglect more expensive than before.

An underappreciated risk is cognitive overload. When financial systems become fragmented, people default to short-term thinking simply to reduce mental strain. This is not a discipline problem; it is a design problem.

Those who adapt well tend to simplify aggressively. Fewer accounts, clearer cash flow visibility, and deliberate automation create mental space for better decisions. The value of money here is inseparable from clarity. When finances are understandable, they become usable.

Why Higher Income Alone Is No Longer Enough

Income growth remains important, but it is no longer a reliable proxy for security. Rising housing costs, healthcare expenses, and regional disparities mean that earning more does not always translate into feeling safer.

This is where many narratives fall short. They celebrate income milestones without addressing structural leakage. Without intentional management, increased earnings often expand lifestyle costs faster than resilience.

Financial stability emerges from alignment:

- Income that matches cost-of-living realities

- Expenses that scale intentionally rather than automatically

- Savings that reflect risk exposure, not generic benchmarks

This alignment explains why some moderate earners feel confident while higher earners feel trapped. Money’s importance lies in how well it supports the actual environment someone operates in, not an abstract standard.

The Psychological Dimension Most People Ignore

Money’s psychological impact is often underestimated because it is invisible when things are working. Yet financial stress subtly alters behavior, decision-making speed, and risk tolerance.

Research consistently shows that scarcity narrows focus. When money feels tight, people prioritize immediate relief over long-term benefit. This is not a personal failing; it is a cognitive response. Adequate financial buffers widen perspective and restore patience.

This insight changes how progress should be measured. Improving finances is not only about future outcomes but about present mental bandwidth. Money matters because it affects how clearly people can think about everything else.

When Money Is Less Helpful Than Expected

Despite its importance, money is not a universal solution. More resources do not automatically produce fulfillment, alignment, or purpose. In some cases, excess focus on optimization creates anxiety rather than relief.

This limitation is rarely addressed honestly. Money solves constraint problems, not meaning problems. It can enable better choices but cannot decide which choices matter.

Recognizing this boundary prevents misallocation of effort. The goal is not to extract maximum value from every dollar, but to ensure money supports life rather than dominating it. That distinction marks a mature relationship with finances.

Adoption Trends and Real-World Shifts

Across the US, UK, AU, and EU, observable patterns are emerging:

- Younger professionals prioritize liquidity over illiquid assets

- Freelancers build larger cash buffers than previous cohorts

- Skill investment increasingly competes with traditional savings

These shifts suggest a collective recalibration. People are responding to volatility not by disengaging, but by redefining what financial success looks like. The emphasis is moving from accumulation to adaptability.

This is often worth exploring for individuals whose careers are tied to fast-evolving fields or location-independent work.

Internal Knowledge Pathways Worth Exploring

Readers often continue this topic by exploring related financial decisions, such as:

- How emergency funds differ for salaried professionals vs. freelancers

- The role of skill investment in long-term income resilience

- How lifestyle inflation quietly erodes financial stability

These areas deepen understanding without requiring radical changes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is money more important now than a decade ago?

Money matters more today because individuals bear greater financial risk due to flexible work, rising costs, and reduced institutional safety nets. Personal finances now replace many protections that once came from employers or governments.

Does financial security mean having a high income?

Not necessarily. Financial security depends on alignment between income, expenses, and risk exposure. Many people with moderate earnings achieve greater stability than higher earners with unmanaged volatility.

How does money affect quality of life beyond spending?

Money influences quality of life by reducing stress, expanding choice, and allowing time for thoughtful decisions. Its impact is often indirect but deeply felt in daily autonomy.

Is financial freedom realistic for most people?

In its modern form, yes. Financial freedom today usually means flexibility and control rather than complete independence from work. It is built gradually through consistency and realistic expectations.

What is the biggest mistake people make managing money digitally?

The most common mistake is fragmentation—too many accounts, subscriptions, and platforms without a clear overview. This reduces visibility and leads to passive financial drift.

Conclusion: Money as Quiet Leverage

In 2026, money’s importance lies less in what it buys and more in what it prevents. It prevents rushed decisions, forced compromises, and chronic uncertainty. It creates space for learning, adjustment, and choice in an economy that rarely stands still.

When understood as leverage rather than identity, money becomes a practical ally. It supports stability without promising perfection and enables freedom without requiring escape. For those navigating high-cost, AI-influenced environments, this perspective often marks the difference between reacting to change and shaping it deliberately.

At that point, money stops being the focus—and starts doing its job.